Financial and academic economists are rushing out oaf the woodwork to take sides in the continuing debate about the state of the Barbados economy, the competence of the government, and its ratings by the international rating agencies. What is clear, however, is that the people who matter – the taxpayers – are not getting a true picture of the state of the economy.

Two of those who have taken opposing views on the Moody’s downgrade are Professors Michael Howard, broadly in agreement, and Avinash Persaud, who is opposed. If Professor Persaud’s outburst, as reported on Barbados Today Online (15/6/11) is accurate, he is simply wrong in suggesting that the Moody’s downgrade was ‘an irresponsible rush to judgement.’ Where is the evidence?

What should they have waited for, more soothing words from the minister of finance and his backers, asking citizens to accept in good faith that the economy is in good shape, but not providing any sound evidence to back it up. Professor Persaud, a member of the prestigious National Council of Economic Advisors, is either speaking as an objective economist or as an economic advisor to the government, an insider. He has to make clear his position. He is reported as saying: “I have no doubt that Barbados will repay its debts and so I believe the decision of Moody’s is an irresponsible rush to judgement, especially given the recent decision of Standards & Poor’s to hold our credit rating steady.” Where is the beef? If Moody’s is rushing to judgement, then where is the counter evidence, the facts to substantiate Professor Persaud’s apparent position that Barbados would repay its debts? Does he know something that the rest of us do not?

The other expert dragged in to the discussion was Professor Justin Robinson, who heads the school of management at Cave Hill. In a statement of fact, he pointed out that if the rating given by the credit rating agency meant that if Barbados was at an investment level, then the market would decide whether or not to buy Barbadian bonds or make loans to the government. Nothing wrong with this. But remember this is the Professor Robinson who is (or was) a senior member of the board of the national insurance scheme who was asked by the late prime minister David Thompson to reply to a valid criticism I had made of the NIS and whose considered reply could be summed up simply as waffle.

Moving on, let us take some of the obvious and most urgent questions: what is the true extent of the current account deficit? Let me explain: despite all the technical jargon by people with an alphabet soup of letters behind their names, the answer is simple: if Barbados imports more than it exports, if it spends more than it earns, it is in deficit; if it spend less than it earns, then it is in surplus.

Why cannot our leading economic spokespeople, especially those who appear, to my mind, to be apologists for the inept way the economy is managed, explain this and give a roadmap for reducing it? Let is also look at the fiscal deficit: governments do not work and earn money; what they spend they raise in taxation such as income tax and sales (VAT) tax. Liberal democratic governments tend to spend more than they earn, stretching the payment over a given period (the length of a parliament) or even across generations.

The decision to spend is based on economic, social and political beliefs. For example, Sir Grantley Adams’ government believed that a modern Deep Water Harbour would bring such economic benefits to Barbados that the decision to borrow the money and stretch repayments over generations would benefit all Barbadians.

What is important is the percentage rate at which that money is borrowed. If government raids the national insurance account as its own piggy bank, which they all tend to do, then the money comes at a virtual nil rate; if they borrow from local banks, then the rate can be negotiated down. The going rate is 15 per cent, according to the Ministry of Finance, which is huge.

On the other hand, government can issue bonds (also called gilts or Treasuries in the US), in which investors ‘loan’ money to government (or big corporations) on a promise to pay in a future date at an agreed rate. In exchange for this, the investor will be given an interest rate, sometimes called a coupon or income, and at a pre-determined time the full amount will be paid back, this is a contractual obligation.

Bonds are an efficient way for government to raise cash and can be very efficient also for some corporations, such as life insurance companies and other annuity providers. So, if a pension provider knows that in ten years’ time X number of new pensioners will be coming on stream, they can guarantee that money by taking out a government bond, hoping the money will be paid in full on the appointed day.

This is where the international credit rating agencies come in. Remember that these are the same agencies that gave top investment-grade ratings to the main players, such as Lehman Brothers, who caused the 2007/8 global financial crisis. They are not perfect. However, at the top of the tree in terms of these ratings is the US dollar, on the assumption the US government will never default on payments, as the Argentinians have done. Of course, we now know that the US economy is on a cliff and if Congress fails to agree a measure by August 3, then the world will be plunged in to further economic disaster.

So, a country which gets a low rating from these agencies (S&P, Moody’s and Fitch are the three leading ones), could still get a loan on the international capital markets. But the rate will be massive – instead of base rate plus three or four per cent, it would be in double digits (as it is now for Barbados).

Let us now look at the key drivers of the economy. There are three key drivers: consumers, corporations and government. Ideally, an economy driven by consumer demand is in a good place. It means firms providing goods and services are making money, therefore they can upgrade their plant and hire additional staff; government would also get more income and sales tax, along with additional revenue from land tax, stamp duty etc.

The important thing here is the rhythm of the business cycle. If disposable income drops for whatever reason, say inflation, then consumers have less to spend, shops and trades people have less work, and government revenue is similarly reduced.

To stimulate the economy, government may ‘invest’ more in public works to keep people in work, hoping that they would go out and spend. (So, already you see a contradiction in liberal democratic macroeconomics: the desire for people to save more for the long term, while at the same time hoping they would spend more to keep the economy working).

Let is assume that government has borrowed $400m at 15 per cent, which means that it has to repay that money in an agreed time, or face penalties, plus an additional £60m in interest rates. In a small economy that $60m can fund any number of projects, so a political – not economic – decision must be made whether or not to go ahead with the loan.

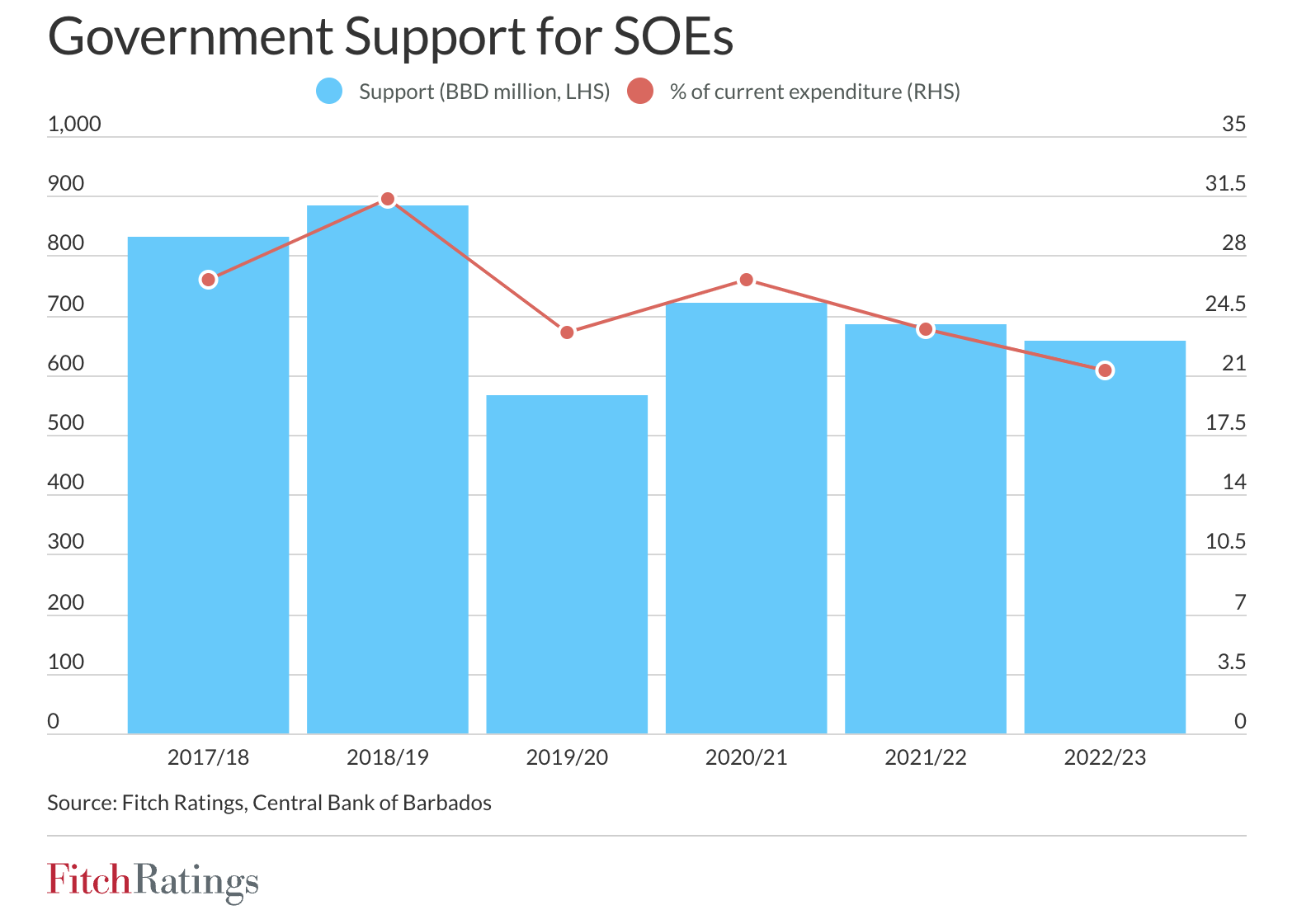

Barbados has lots of deep structural problems: the long-term unemployed, who are in reality unemployable; a lack of funding for small businesses due to foreign-owned banks not lending and government not having the guts to turn the eighteen post offices in to conventional retail banks, offering a basic balance sheet service; the meltdown in the school system and its high failure rate; the social housing mess; the health care system; the crisis in the civil and criminal courts; civil servants squatting at their seats with a productivity rate of near zero; a massive public payroll for inefficient and unprofitable agencies, such as the Transport Board; the list is endless.

All this is topped by a government going cap in hand to the Chinese begging them for crumbs to repair an old cinema and to help set up a small business funding scheme. How embarrassing. Presumably this is an idea that came from the National Council of Economic Advisors.

The Barbados government and the central bank, and now the National Council of Economic Advisors, have a lot of explaining to do about the state of the economy, until then Moody’s are right and the ungrounded optimism of S&P is wide of the mark. In the final analysis, we all wish Barbados well and badly want the nation to progress, but don’t try to pull wool over our eyes.

Leave a Reply to CloneCancel reply